Impacts to People and Communities

Building Materials Can Harm Families and Communities

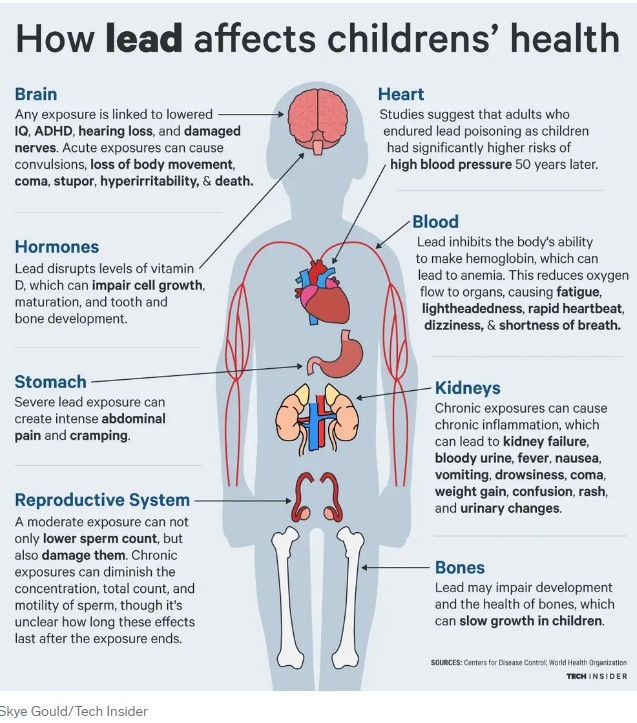

Many chemicals used in building products that make up our indoor spaces are known or suspected to cause long-term harm to human health. Lead and asbestos are examples of chemicals that were widely used in building products until their devastating health impacts were recognized. While the presence of lead and asbestos in our building products have since been deemed unsafe in the U.S. and policies have been created to control their use, remediation efforts are ongoing and incomplete. Communities are still struggling with lead pollution decades later, especially low-income and minority households. There are other chemicals still being manufactured into our building products that pollute the environment and our dwelling spaces, and pose health risks to families and communities.

There is an ever-growing body of evidence that illustrates that certain chemicals used in building products can negatively affect the health of residents and workers, with people of color experiencing disproportionately more exposures and health harms than white people. Higher instances of asthma, adverse birth outcomes, childhood obesity, hypertension, and diabetes occur in communities of color, correlating with higher amounts of heavy metals, phthalates, and VOCs. This illustrates the need for policy makers and leaders in manufacturing, and the building industry to work together to create safer spaces for all residents and installers, especially those most vulnerable.

Building with products and materials that are certified to contain less hazardous chemical content—combined with proper ventilation strategies—can greatly improve a building’s indoor air quality (IAQ) by reducing the amount of chemicals found in the indoor environment, and allowing for pollutants to be flushed out with incoming fresh air. This could mean a reduction in the development of chronic health conditions, as well as alleviation of symptoms from asthma and other respiratory conditions, especially for People of Color. According to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, Black and Puerto Rican populations are nearly 1.5 times more likely to have asthma, and 3 times more likely to die from it. Addressing the link between unhealthy indoor environments and asthma rates could itself have widespread impacts for generations to come.

How Harmful Chemicals In Building Products Affect Our Health And Bodies

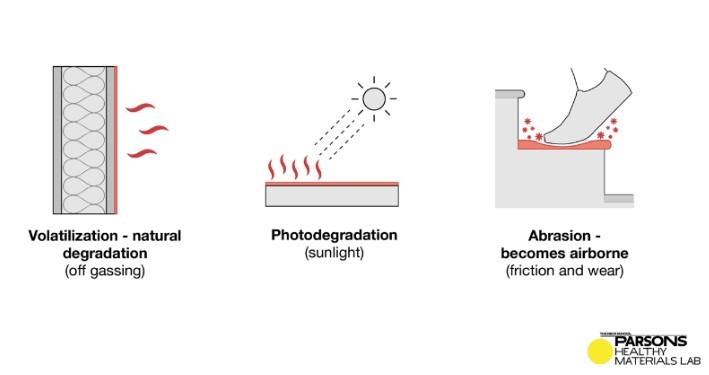

Buildings that are built with products containing hazardous chemicals can create an unsafe environment for residents. Many chemicals that are manufactured into building products do not remain safely encapsulated over the course of their product life. Instead, chemicals migrate out of building products and find their way into the indoor environment via construction processes, volatilization, and degradation of products. Dust, indoor air, and tap water become new hosts for these migrated chemicals, subsequently ending up in our bodies with the power to harm the body’s health.

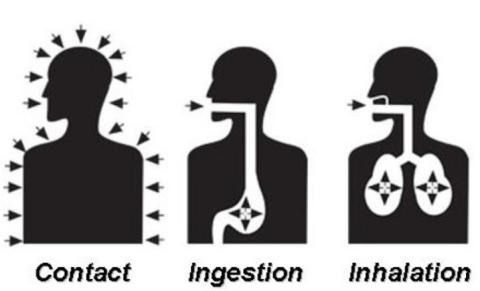

The chemicals in building products can enter our bodies through breath (inhalation), our mouths (ingestion), and our skin (absorption). When people are exposed to hazardous chemicals, they can be harmed when the chemical interacts with their bodies’ systems and organs.

Chemicals can negatively impact human health by surfacing as short-term effects and chronic or long-term health conditions. Acute symptoms from chemical exposures can include headaches, dizziness, rashes, and eye irritation. More severe acute symptoms can include chemical burns, allergic reactions, or the triggering of an asthma attack.

Long-term health conditions can develop over time from exposure to one or more hazardous chemicals. In these cases, chemicals cause damage to a person’s organs or internal systems, which can result in conditions and diseases that include cancer, asthma, infertility, impotence, hypertension, reduced I.Q., obesity, birth defects, and other adverse birth outcomes.

The risk of developing health problems from a chemical exposure will depend on the type of chemical and its toxicity—the amount of a chemical a person has been exposed to, the length of time a person has been exposed, and the amount of times the person was exposed. For example, installers who work frequently with a similar group of products with known health risks, and occupants who spend a large percentage of time in their home, are at a greater risk of exposure to chemicals that may be present in certain building products.

Vulnerable Populations

Housing is a human right, and everyone regardless of race, age, gender, income, sexual orientation, or disability status should have access to affordable housing that promotes health and wellbeing. Unfortunately, this is not the lived reality for many people in the U.S. with low-income who have navigated the affordable housing system and may have dealt with substandard housing conditions, discrimination, and limited access to resources.

The presence of hazardous chemicals and pollutants in our homes can affect anyone, but it can be more detrimental for the following populations:

- Children and the elderly;

- People with respiratory conditions such as asthma;

- Those with weakened immune systems;

- Those with limited access to health care;

- People with low income;

- Historically disadvantaged, disenfranchised, and marginalized groups; and/or

- Those living in older or degraded homes that may still contain hazardous materials such as lead, paint, or mold

For vulnerable populations, an indoor environment containing allergens, pollutants, or hazardous chemicals may result in more severe health outcomes, especially if they have pre-existing medical conditions, a weakened immune system, or limited access to healthcare.

How Children’s Health is Impacted

Young children are not just shorter adults. They eat, drink, and breathe more pound for pound. So if there are toxic chemicals in the home, children will be more exposed than adults. Infants and toddlers also spend more time closer to the ground and put their hands and whatever is in their hands in their mouths more often. In addition, childrens’ bodies are rapidly developing and more vulnerable to any chemical interference. The first 1,000 days between a person’s pregnancy and their child’s second birthday offer a unique window of opportunity to health and how successful they will be in life, and exposure to environmental hazards during that time compromises that. All of these factors add up to a strong need to protect children from the toxic chemicals in building products.

Not all children face the same level of chemical exposure threats. Young Black children, for example, have higher blood lead levels and are more likely to live in low-income communities with chipping lead paint and lead in their drinking water. Black babies are also more likely to be born prematurely, a condition that can lead to lifelong health issues and is linked to the higher levels of air pollution in predominantly Black communities and higher levels of lead and phthalates in Black women.

The Policies and Practices Behind Disproportionate Exposures to Harmful Chemicals

Why are people of color exposed to more harmful chemicals in housing? The United States housing system is interwoven with systematically racist practices and policies that forced people into living in communities burdened by pollution and substandard housing. These four policies and practices fueled inequality in American housing that can still be felt today.

Federal Housing Administration (FHA)

The FHA is one of the largest mortgage providers in the world. It provides mortgage insurance on single-family, multifamily, and manufactured homes in the United States. During the 1940s, the FHA systematically denied services such as mortgages, insurance loans, and other financial services to residents based on race and ethnicity. Black families along with other marginalized communities without access to these mortgages and loans were left with no financial mechanisms that would assist them in their attempt to move from their neighborhoods in what became known as “redlined.”

Redlining

Redlining is a discriminatory practice that consists of the systematic denial of services such as mortgages, insurance loans, and other financial services to residents of certain areas based on their race or ethnicity. According to the Federal Reserve, the term “redlining” originated in the 1920s and 1930s when the U.S. government created homeownership programs. Lenders would draw red lines around areas on maps to indicate neighborhoods where they would not make loans. Those areas were where most communities of color lived.

Formerly redlined communities like Newark, New Jersey continue to be victims of environmental injustice and inequality through air pollution, specifically from diesel particulate matter from freight and hazardous waste sites. Redlined communities can be up to fifteen degrees hotter than non-redlined communities. This is significant not only because low-income communities have fewer means to keep themselves cool, but because new-but-developing research shows that high heat can increase volatilization of certain building products ultimately worsening indoor air quality in the home.

G.I. Bill

After World War II, the G.I. bill was created to assist veterans in readjusting to normalcy. Black veterans were unable to use the housing provisions in the GI bill because banks generally would not grant mortgage loans in black neighborhoods. If a Black family were to try to move to white suburban neighborhoods, they would often be excluded through a mix of deed covenants and informal racism. The G.I. bill enabled white families to flock to the suburbs to start new lives, disinvesting the urban neighborhoods they left behind.

American Housing Act of 1949

The American Housing Act of 1949 was created to revitalize urban cities after the exodus of families to the suburbs commonly referred to as “white flight.” While the intent of this act may have been honorable, the use of eminent domain authorized under the Act allowed the government to buy out communities often occupied by people of color and displace them to accommodate urban renewal that benefited white communities. Federal urban renewal programs from the 1950s to the 1970s displaced more than 300,000 families across the country, disproportionately razing Black neighborhoods in favor of commercial and industrial development.

Why Low-VOC, Formaldehyde-Free, and Phthalate-Free Matters

Why Low-VOC Matters

Volatile organic compounds are mixtures of chemicals (compounds) made of carbon (organic) that can be released into the air under normal conditions of temperature and pressure (volatile). Building products that contain chemicals classified as VOCs emit hazardous gasses that can be breathed in first by the workers installing the product, and then by the families who live with the products in their home. Some examples include cancer-causing formaldehyde—which is often found in particle board—and toluene—found in oil paint—which can harm a woman’s reproductive system. VOCs can harm our health, and low to no VOC products should be selected.

Why Formaldehyde-Free Matters

Formaldehyde is used to hold together the wood chips that make up composite wood products like particle board and plywood. It can also be used as a binder in carpeting, engineering wood and laminate flooring. Because formaldehyde is a VOC, the chemical can get out of the product and cause health problems.

Short-term effects of formaldehyde include skin and eye irritation and allergic reactions. Long-term exposure can lead to cancer. Formaldehyde is also suspected of causing birth defects and impacting the endocrine system and its hormones that control metabolism, development, growth, reproduction, and behavior.

Why Phthalate-Free Matters

Phthalates (pronounced THAL-ates) are a group of chemicals used in vinyl flooring, carpet backing and wall coverings and adhesives and sealants. Phthalates are plasticizers that make building products more flexible. But phthalates are VOCs that can come out of the product and get into our bodies.

Phthalates like Di (2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) are endocrine disruptors—meaning these chemicals interfere with the normal workings of the hormones in the endocrine system. This interference can harm fetal and infant growth and development, and can determine whether that baby can become an adult with a healthy reproductive system.

Energy Efficiency Maintains a Healthier Indoor Environment

Energy-efficiency in buildings provides several benefits to owners and occupants, and is a matter of health and equity as much as it is a matter of resource saving. Investing in a building’s improved energy efficiency through air sealing and insulation lowers energy bills, increases a building’s durability, and creates a healthier indoor environment by optimizing humidity and temperature levels. Maintaining optimal humidity levels is important because it reduces the risk of dust mites and mold growth, and offers benefits such as soothing the respiratory system and preventing dry skin in the winter months. An airtight house combined with proper ventilation improves indoor air quality by reducing contaminants like dust, mold, and outdoor pollution.

However, as energy efficiency measures increase, and we build our houses to be more airtight, chemicals that leach out of building products will contribute to the pollution of indoor air quality. This highlights the importance of choosing healthier building products in weatherization work, as well as the importance of ventilation systems with MERV 13 filters or higher.

We have a long way to go in ensuring that all people share in the safety and comfort of having a healthy, energy-efficient home. The cost of energy disproportionately burdens the poor and can account for up to 20% of their income expenditure, a significantly higher proportion than middle or high income earners. An estimated 30 million affordable housing units are considered substandard because of physical or health hazards, including asthmagens and lead, along with gas leaks and inadequate heating systems. These homes often have poor energy efficiency as well. Over 60% of low-income renters are people of color.